Bond. James Bond. Is there a name more synonymous with spying, tuxedos, and shaken cocktails than the British secret agent? Join me as I read all of the James Bond books in 007 Case Files, encompassing Ian Fleming and beyond. For Your Eyes Only: there’s potential spoilers ahead.

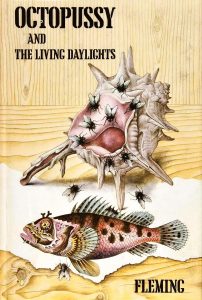

Ian Fleming’s fourteenth and final James Bond book is a collection of short stories. OCTOPUSSY AND THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS, published almost two years after the author’s death, follows the posthumous publication of The Man with the Golden Gun. Where that left readers on a sour note of a disjointed narrative, this collection returns to some of the stronger writing found in the previous shorts collection, For Your Eyes Only.

On its initial publication in 1966, only the titular stories were included in the slender volume. Subsequent pressings have included a small collection of other tales – “Property of a Lady” and “007 in New York” – both of which were first published in 1963. Taken together, they form a curious thematic set as Bond alternates between introspection, voyeurism, and tourism.

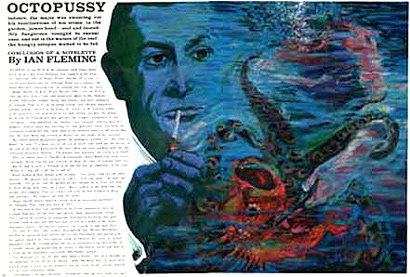

“Octopussy” first appeared as a serial in the Daily Express, and like the eponymous cephalopod, it’s a curious creature. Along with Pussy Galore, it’s arguably one of the most famously named Pussies in the Bond universe. Like some of the other Bond shorts, the spy is not the focus of the piece. Instead, his target Major Dexter Smythe gets much of the attention. As a former hero of the Second World War, the Major finds himself in Bond’s sights when the body of a figure from Bond’s youth turns up in the Austrian mountains.

Like the short story for “Quantum of Solace,” Bond mostly serves as a catalyst for a flashback. In Smythe, we have something of an opposite number to 007. While their background may have some similarities, his choices and past sins give him something of a moral ending. Author and journalist Sam Leith (writing in the 2012 Vintage edition) notes that the narrative voice of the short “watches him as you’d watch an interesting fish in an aquarium.” His greed and pride over his prize possession is his ultimate undoing.

Bond gives away a glimmer of humanity in this tale, reflecting that the man Smythe killed was “something of a father to me at a time when I happened to need one.” It’s another one of the rare glimpses into Bond’s upbringing, one that found its way into the film Spectre. Yet it’s “The Living Daylights” that really offers up a different side of Bond. In the short story, Bond is tasked to take out a KGB sniper, and stakes out the assassin from a building across the road in East Berlin.

Over the course of three nights, Bond is unsurprisingly distracted by an attractive woman with a cello. While the two elements come together in a dramatic fashion, it’s Bond’s inner thoughts that might surprise. After contemplating what a simple life “within easy reach” the girl lives, Bond tells off his minder, Captain Sender, who is in the process of chastising Bond for drinking a stiff whisky on the job:

“‘Look my friend,’ said Bond wearily, ‘I’ve got to commit a murder tonight. Not you. Me…Think I like this job? Having a Double-0 number and so on? I’d be quite happy for you to get me sacked from the Double-O Section.”

It’s certainly not the first time Bond has considered another life. He wrote his resignation in Casino Royale. And again in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. We got a sense of his nihilism in Moonraker, and our hero expressed a weariness of death in Goldfinger. Here, even M “didn’t like sending a man to a killing.” Even at the height of Bond mania, Fleming has no qualms in bursting the bubble of the glamorous life of a spy.

“The Property of a Lady,” which actually made its way into the film adaptation of Octopussy in 1983, was originally commissioned for auction house Sotheby’s 1963 journal, The Ivory Hammer. Suspecting the Resident Director of the KGB will be in London to underbid on a Fabergé egg, Bond attends the auction to identify him. What Fleming does so well here is use the form of an auction to create the same tension he gains from a card game as a set piece. The gamification of his job that something Bond reflects on in this short: “In the grim chess game that is Secret Service work, the Russians would have lost a queen.”

“007 in New York” throws the expected shade at America that one would expect from Fleming, despite originally appearing in the New York Herald Tribune in October 1963. Food gets a major dose of Bond’s skepticism, but he curiously considers visiting a S&M club. “As with the transvestite places in Paris and Berlin,” he muses, “it would be fun to go and have a look.” The incredibly wry tale is a surprisingly amusing bookend that reveals one of the greatest bits of Bond trivia of all time: his recipe for scrambled eggs! (If you’re wondering, it contains a whopping 12 eggs, 3-5 oz. of butter, and a dash of salt and pepper).

Which might just be the common thread throughout these stories. The eggs, like his particular recipe for a martini, reveal a stoic and workmanlike fastidious Britishness that comes with Bond’s job. He may tire of killing, but his human quirks remain in the face of those odds. Which might be why these stories – filled with casual racism, sexism, and privilege – continue to appeal after all these years. To quote Annie Hall, “They’re totally crazy, irrational, and absurd, but we keep going through it because we need the eggs.”

James Bond will return…in Colonel Sun.